In his black rexine bag, says Murari Lal, he has been carrying his world around for the past five years, making several stops along the way — most of them at examination centres. The contents include a gamcha, an umbrella, a mat, a folder with his BA and MA marksheets, a mobile charger and the admit card for the Group D Railway Recruitment Board Exam he will be taking in two hours.

There is another thing he carries to all exams, he says: “Ummeed (hope)”; hope for a government job.

This time his halt is the footpath outside the swanky building of the Tata Consultancy Services iON Digital Zone in Noida’s Sector 62. It is the biggest exam centre for the “world’s largest recruitment drive”, being conducted by the Indian Railways.

Lal arrived the previous night, over 12 hours before his 4 pm test. “I don’t know anyone in Delhi-NCR and so decided to wait on the footpath.”

Before the 4 pm test, over 3,000 move towards the entrance gate in a wave, holding on to their admit cards

Before the 4 pm test, over 3,000 move towards the entrance gate in a wave, holding on to their admit cards

He has just stretched out on his mat to grab some rest when the second batch of candidates walks out after the 12.30 pm test. Hearing murmurs about the question paper being “very difficult”, Lal decides to get up. “I should go over my notes and previous years’ question papers again,” he says, flipping through his well-thumbed copy of ‘Arihant Railway Exam Group D — Solved Papers’.

READ | ‘It appears the entire country is here’

Of the 2.37 crore people who applied for the exams this year, Lal is part of the largest chunk,1.9 crore, vying for the 62,907 Group D posts — of cabinman, keyman, fitter, leverman, gangman, pointsman, porter, helper, switchman, trackman and welder.

Tests are held online in three shifts every day (9 am to 10.30 am; 12.30 pm to 2 pm; 4 pm to 5.30 pm). In every shift at this Noida centre, 3,450 have been taking the test — a 90-minute, multiple-choice paper, covering Maths, General Intelligence and Reasoning, Science and Current Affairs — since September 17, and will do so till December.

Anyone who has studied up to at least Class 10 is eligible. At 31, Lal, an SC category candidate, still has a few more chances left. But today, that is not much of a consolation. Looking at aspirants milling outside the TCS building, who have taken over roads, footpaths, even a traffic police stall, who ignore the slight drizzle to pore over their books, who take guilty breaks to watch YouTube videos on phones, or defiantly climb onto an elevated structure to take selfies, Lal says, “It appears the entire country is here.”

Lal also understands why. A BA in Sociology, an MA in English, he says he started appearing for competitive exams in 2013, while taking tuitions and working off and on at a factory in Chandigarh. “In 2013, the UP Police exam I appeared for got cancelled after a paper leak. In 2016, I was on the waiting list for a government teacher’s job, that didn’t materialise. I didn’t clear the previous railway exam either,” he lists.

He wishes politicians focused on unemployment, instead of non-issues. “Hindustan ka neta dalaal hai. Berozgaar naujawan dhakke kha rahe hain (Politicians just make money. Unemployed youth keep struggling).”

And wonders why, unlike last time, he didn’t get a free pass to travel to the centre, issued by the Railways for SC/ST candidates.

But Lal keeps going. Explaining why, the second of four brothers, all of them daily wagers, quotes poet Sohan Lal Dwivedi, “Lehron se dar kar nauka paar nahin hoti, koshish karne waalon ki kabhi haar nahin hoti (A boat can’t cross the sea fearing the waves; one who works hard can’t lose).”

“I failed my BSc. What other job can I get?” says Jitesh Kumar, 18, occupying another portion of the footpath, which is a little wet from the drizzle.

Kumar says he couldn’t focus on studies after his father’s death last year. “He had a samosa cart, selling two for Rs 5. Now I do that,” says the eldest of three siblings.

Kumar heard about the railway exam at the local cyber cafe near his native village in Baghpat, western Uttar Pradesh. “The bhaiya there informs us about government jobs,” he says. With the cart only fetching about

Rs 1,500 per month, the 18-year-old decided to venture out for his first trip to Noida.

Squinting his tired eyes, he says, “I came here yesterday and have been sitting outside since. The admit card says we have to be here a day in advance, but there are no arrangements, no toilets, no water… My exam is at 4 pm, still a few hours away.”

The morning only left him more despondent, Kumar adds. “I didn’t expect so many people, it seems very tough to crack this exam… Maybe I will try for an Army job… Several men in my village are in the Army.”

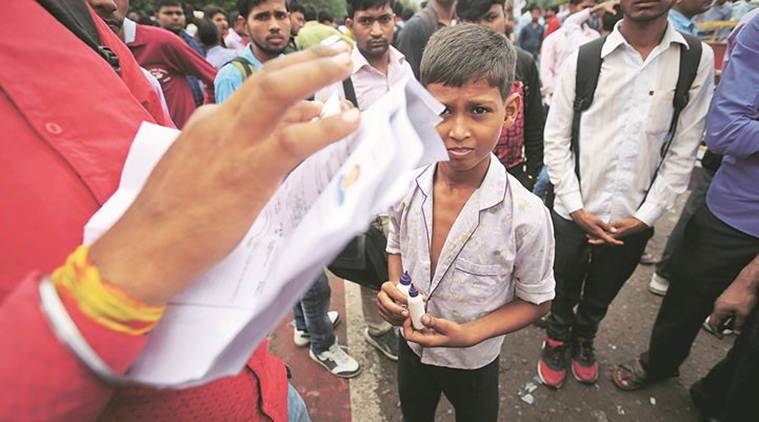

Vishal, 9, selling glue to candidates at the centre; Rs 5 for one-time use

Vishal, 9, selling glue to candidates at the centre; Rs 5 for one-time use

Waiting near Kumar is Mohammad Farooq, 21, also from Baghpat, who says he has tried to get into the Army several times. Unlike Kumar, who couldn’t afford coaching, Farooq, an MA student, has come fortified with three months of training at an “institute”, paying Rs 5,000.