The European Space Agency (ESA) has announced its investigation for Earth’s enigmatic twin Venus, only days after NASA agreed to deploy two missions to the planet. EnVision will be the next spacecraft to orbit Venus, offering a comprehensive picture of the planet from its core to its high atmosphere.

The European Space Agency has chosen the Envision probe to investigate the second planet from the Sun. ESA announced the news a week after Nasa, the American space agency, chose two Venus projects of its own, Veritas and Davinci+.

The destination isn’t the only point of convergence; Europe and the United States will also contribute hosted instrumentation to each other’s efforts.

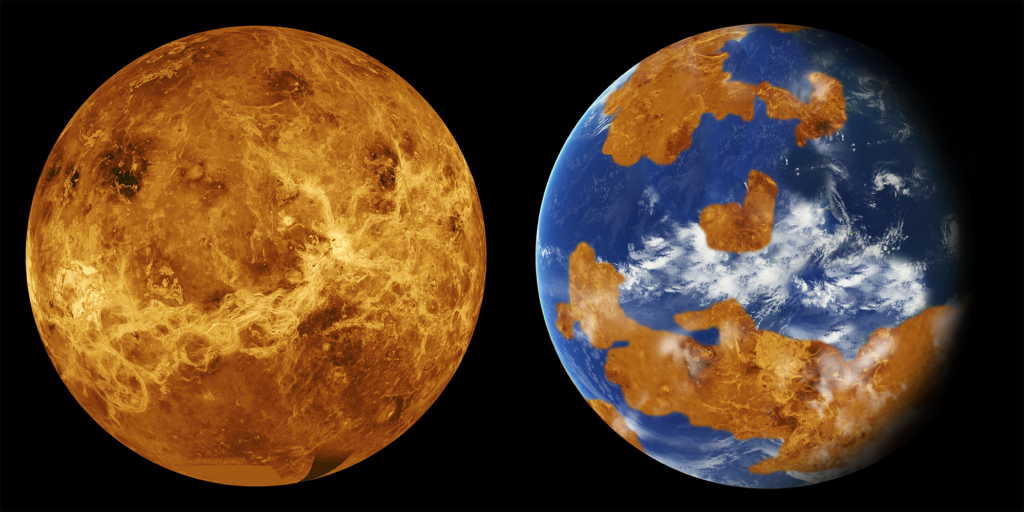

Venus is frequently referred to as Earth’s “evil twin” (inaccurately). It’s nearly the same size as our home planet, and it’s scorching hot and arid. It’s nothing like the beautiful blue orb we call home. The discovery of phosphine in Venus’ clouds by a group of astronomers sparked renewed interest in the planet.

This chemical may have a biological origin, leading to the hypothesis that microbial life may exist at lower elevations on the planet. With more research, the phosphine observations have lost their persuasiveness, although many people still think Venus is a wonderful place to explore. And it’s because of this dramatic contrast that all three missions will attempt to address the question.

Such a find would also reveal something about tectonics, the giant rocky engine that perpetually recycles Earth’s outer layers while also assisting in the regulation of a habitable temperature. The new Venus missions will help determine if and to what extent this engine has worked on Venus throughout history. Six experiments will be carried out by Envision.

A synthetic aperture radar will be the primary sensor, piercing the planet’s thick clouds to map surface details down to a resolution of 10m per pixel. A second radar will detect structures below the surface to a depth of a kilometer.

Three of the remaining four instruments are spectrometers that will search for hotspots on Venus as well as track gases in the planet’s atmosphere. There appear to be hundreds of thousands of volcanoes, based on prior missions. The mission team is interested in knowing how many are still active today.

“Venus is our nearest neighbor and the only Earth-sized planet we can visit,” said Dr. Colin Wilson of Oxford University in the United Kingdom. “We believe it is geologically active. And if that’s the case, why didn’t Venus come out looking like Earth? Or, perhaps a better question is: why didn’t Earth grow in the same way that Venus did? How come we got the habitable climate?”